The problem with a premise

It is hard to avoid the allure of a good premise, after all,

the premise is where the fun is. For those of us who care to create and tell stories,

we can confuse the premise as being the most important factor in success. The premise

should not be the unique selling point of a story. Premises can be wildly

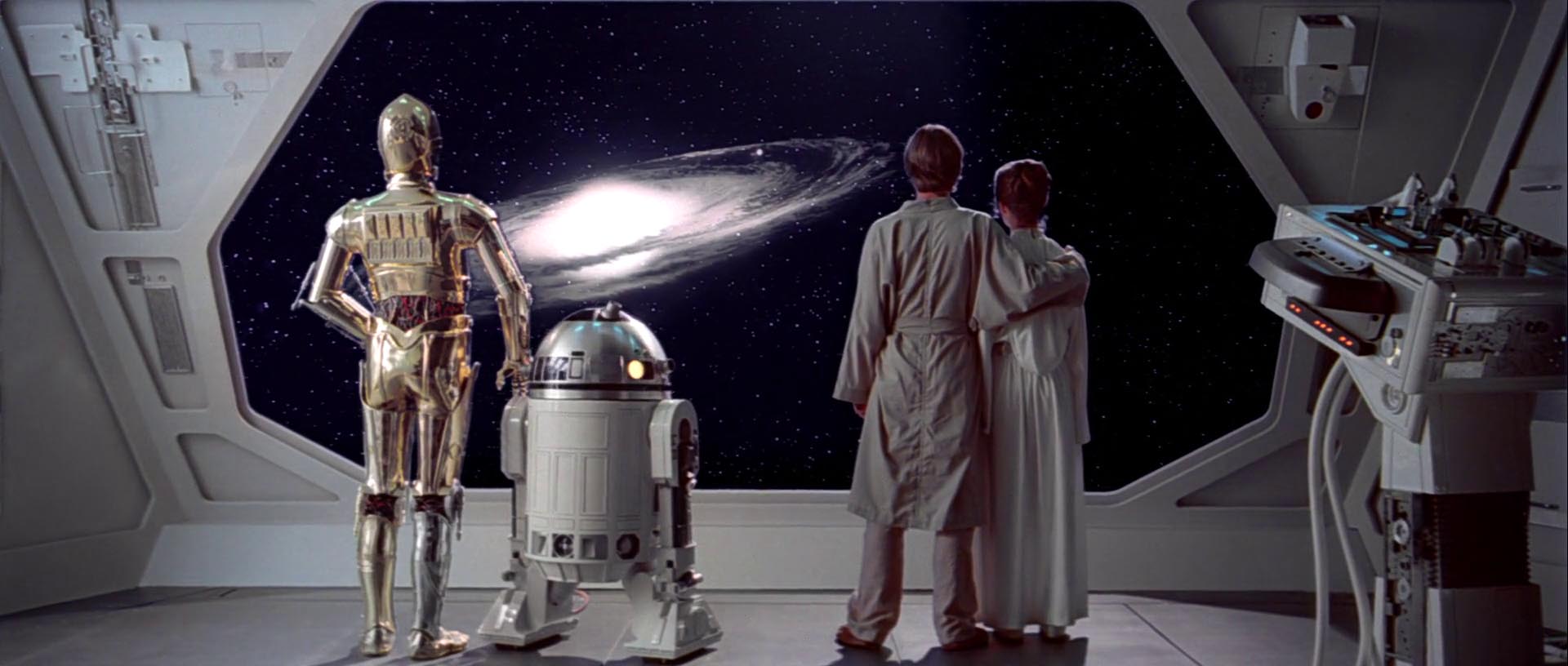

different, but stories can remain the same. The hero’s tale, for example, has

been applied to a whole host of different settings, but the narrative structure

of the story remains largely intact, regardless of being set in the wilds of

space or the closet of an office.

When we ask the question, “what is this about?” the response

is normally a version of the premise, but this isn’t the point of the art… that’s

not what it’s about. The Babadook film, you might say, is about a monster who

is haunting a poor family, but the film is more truly about the monster that is

grief, and the effect it has on those left behind who have to fight it’s insidious

crutches. But I suppose that doesn’t fit on a poster as well.

Conceiving a good premise is too easy a distraction. A good

premise is low hanging fruit for expressionism. It is the easiest thing to do to

apply a coat of fantasy, it is much harder to create the body of a point, a

purpose. In creating art, you should ask yourself, repeatedly, what is the

point of this? What opinion is it that I have, or even just wish to consider? Once

you know this, you can start thinking about premise and narrative devices.

I think that classical art probably understands this idea of

creation most. Anybody might photograph a landscape or paint an attractive

woman, but we are drawn in when we think about the further meaning in the illustration.

For story tellers, meaning isn’t there to found, it is conceived. And that is the

challenge.

Comments

Post a Comment